How Reagan empowered creationism, undermined science education, and reshaped the American political landscape.

“Nothing has ever been more insupportable for a man and a human society than freedom.” — Ivan Karamazov, The Brothers Karamazov

“The path up and the path down are one and the same.” — Heraclitus

After the cataclysmic blast that brought down Mount St. Helens’ North Face in the spring of 1980, the volcano settled into an uneasy stillness, as if taking its seventh day for sabbath.

But Vulcan had not finished with his forge.

In August, the volcano awoke again—stretching, exhaling—and then let loose a new series of ash-laden bursts, beginning the slow, hard work of reshaping its blasted heath and raising a new crater dome.

That same August—two centuries after Washington forged resolve in a winter valley1 with Cato’s Stoic fire—Ronald Reagan found it fitting to raise a few questions. Questions designed to reshape a nation—questions whose unwitting effect was to erode the common epistemic ground on which democracy depends.

That August, Reagan stood before ten thousand twice-born evangelical Christians and professed that he had “a great many questions” about the theory of evolution.

What’s the harm in asking a few rhetorical questions? Power’s got to be got somehow.

Doesn’t it?

As the ever-charming man campaigned for office, he looked into the teleprompter, smiled his avuncular smile, and read two polished phrases set in deliberate, nostalgic parallel: “old-time religion” and “old-time Constitution.”

In doing so, Reagan cast a kind of charm—a syntactic spell that reinforced a pernicious myth: that the Constitution and the Bible belong to the same sacred lineage, founding the nation in tandem, the one imagined as handmaiden to the other.

But the Constitution is not divinely inspired. Still less is it inspired by the God of Abraham. It was written by men—men of the Enlightenment who, understanding history, oppression, and endless religious wars, erected a deliberate wall of separation between the two documents. The younger protects the right to read the older after one’s own fashion, and to worship—or not—without coercion from the state.

The effect of Reagan’s rhetoric was to conjure a storm to rival Jupiter’s swirling Red Spot—the ancient tempest first revealed through Galileo’s heretical glass. Its sustained winds have worn down the Wall of Separation, the principle of non-establishment, breaching that barrier for those who see the very idea of religious neutrality as an abomination before God, the absolute ruler of the universe in their eyes, whose laws and commands they believe to be universally binding.

(Is it any wonder that Pete Hegseth, Trump’s newly christened “Secretary of War,” released a video of himself reciting the Lord’s Prayer over a montage of missiles, fighter jets, and saluting soldiers—a piece of propaganda that places military power and old-time religion in deliberate, unsettling parallel?)

But the storm was not blown into public life by Reagan alone. Every moment follows from another. One eruption gives rise to the next. The day presupposes the dawn. Reagan’s morning was long in the making.

To call any moment a beginning is a kind of necessary fiction—one that reifies illusion, as in any story that insists there was a First Day or a First Man. There never was. Even Adam had a bellybutton—and a mother.

The moment that Reagan took the stage had long been quickening.

His political opponent, Jimmy Carter, had been a kind of Johnny Appleseed — a plainspoken Southern peanut farmer who had planted America’s moral and identitarian questions a half-decade earlier. And in seeking to nurture a legacy of his own within the Oval Office, he sincerely and publicly professed his Baptist faith, making the phrase “born again” a household term.

The language was loaded, each word a seed, and that diction helped carry him into office and deliver his message. Yet his open-minded record on feminism, abortion, gay rights, and school prayer disillusioned many who longed to bury the ambiguities and return to traditional Judeo-Christian values.

Freedom is burdensome. Thinking is hard. The moral ambiguities sown in the civil-rights era had reaped too much anxiety—the dizziness of freedom—and the people craved both bread and certainty. They wanted clarity, security, and direction.

Reagan got the angst of the age. He understood how to draw clear lines, how to cast the illusion of clarity—both economic and existential. The people wanted comfort and reassurance. He promised to put bread on their tables. But he knew that man does not live on bread alone.

Though not himself an Evangelical (he was raised a Disciple of Christ), and though he was not as devout as his rhetoric suggested (he rarely attended church), he knew how to speak to the hearts of discontented Evangelicals. At his forge, he brought his hammer down and shaped supple sentences. Out of these, he formed a new crater dome around which they could gather, join hands, and bind themselves into an identitarian political bloc—one that would vote reliably Republican.

So it was that, in August of 1980, at the National Affairs Briefing in Dallas—billed as a conference on “Religious Liberty”—he told a conservative crowd hungry for certainty, “I know you can’t endorse me, but I want you to know that I endorse you and what you are doing.”

A master storyteller, he told them, as he told other fundamentalists, that he could not understand atheists. He told them he had often imagined inviting one to a gourmet dinner and, after they had eaten their fill, asking if they believed in the cook.

Their belly-felt laughter suggested they savored the juice of the joke too greedily to notice the fat in the fallacy.

As his campaign gained momentum, Reagan did not stop at raising his “questions.” He asserted that evolution is “a scientific theory only,” and that “in recent years it has been challenged.”

(By whom? Balaam’s donkey? Ah, the braying virtues of the passive voice.)

Then, paradoxically, he appealed to the very authority whose overwhelming consensus he sought to undermine. He invoked a chorus of phantom scientists and told the audience that evolution “is not believed in the scientific community to be as infallible as it once was.”

(Again, the bray of the passive voice. No sources cited.)

But beneath all that confident rhetoric, there had been no scientific challenge. The theory remained as settled as the heliocentric theory. Even so, he told them that “recent discoveries” had “pointed up great flaws in it”—discoveries no one ever seemed able to name.

The crowd ate it up like a well-marbled, well-seasoned steak. It tasted so good—so rich, so juicy—it simply had to be true.

Then he leaned forward, dangled the keys to the kitchen, and told them that the old-time version of Creation should be taught in public schools, side by side with Darwin’s account.

Across the country, science teachers trembled.

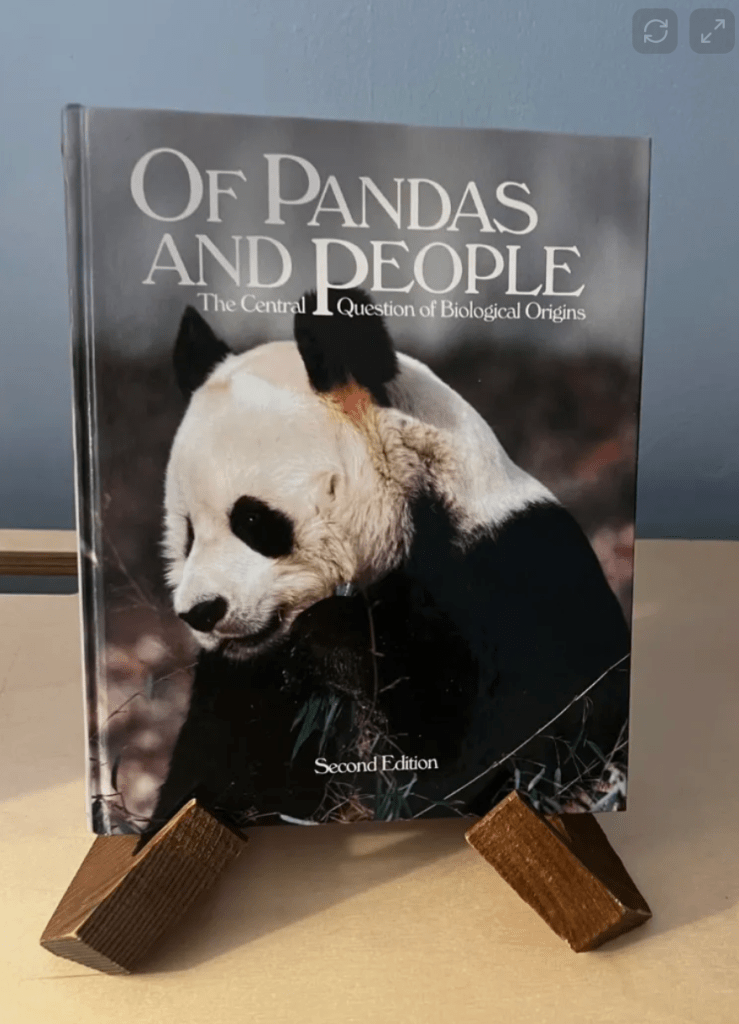

Reagan’s rhetoric gave oxymoronic “creation scientists” a hall pass to “teach the controversy.” Emboldened, they entered the classroom, both-sided the issue, eroded the authority of science, and dulled the American mind.

To this day, these pseudo-scientists mangle basic vocabulary. Just as they wield the word Truth in a peculiar way, they put their ignorance on full display when they claim that evolution by natural selection is “just a theory, not a fact.”

What they do not grasp is that practicing scientists hold the word fact in far lower esteem than the word theory. Facts are cheap. Even the ancients—Herodotus, Xenophanes, Aristotle, Strabo, and Pliny the Elder, whose curiosity sent him running toward Vesuvius as others fled—knew that fossilized sea creatures are embedded in rocks high in the mountains.

A theory explains why. A theory makes sense of the fact.

Aristotle noted that some snakes have “remnants of feet,” but could not say why. Ancient anatomists knew of the human tailbone yet could not account for its presence. Ancient physicians struggled through plague after plague, but were powerless to understand them, because they had no idea that microbes evolve, adapt, and return in new forms.

Darwin’s theory unlocked these mysteries, and much, much more.

As a teacher, I’ve witnessed well-financed campaigns designed to muddy the minds of students. Kids have come to me after weekend retreats with polished pamphlets and slick videos that teach Reagan’s gourmet-cook fallacy and insist that evolution is “just a theory, not a fact.”

At these events—the progeny of Reagan’s rhetoric—kids take classes, attend assemblies, and participate in activities designed to orient them toward a creationist worldview. They learn talking points and scripted pseudo-intellectual questions—questions crafted in bad faith, non-scientific “gotcha” lines forged to undermine the public-school science teacher, not to understand her.

Let that sink in.

Creationists produce literature and host conventions specifically to teach children how to reject science. It’s willful ignorance. It’s organized stupidity—stupidity that casts the educator as the enemy of God.

But it’s an old story. Socrates had no union protection, and we know what happened to him for questioning the state’s gods. And without a proper understanding of science, the public has no protection either:

“I don’t think science knows, actually.” —Trump, September 2020, dismissing the role of human-caused climate change in California’s unprecedented megafires, even as Americans were locked down in a global pandemic.

🌈 If you missed Field Note 3¾ — The Rainbow Connection: Don’t Believe Everything You Think, click here.

🍭 If you missed Field Note 3.2, “All The King’s Candy,” click here.

🎧 Prefer to listen to this piece? Click here.

Valley Forge takes its name from an 18th-century iron forge on Valley Creek—an actual furnace long before the site became a symbol of endurance and national mythology. I first described its symbolic role in Waypoint 3.2, where Washington’s winter encampment frames the chapter’s opening movement. ↩︎

Leave a comment