from Chapter 3, The Blasted Heath

“Wise men talk because they have something to say; fools, because they have to say something.” — Anonymous, often misattributed to Plato

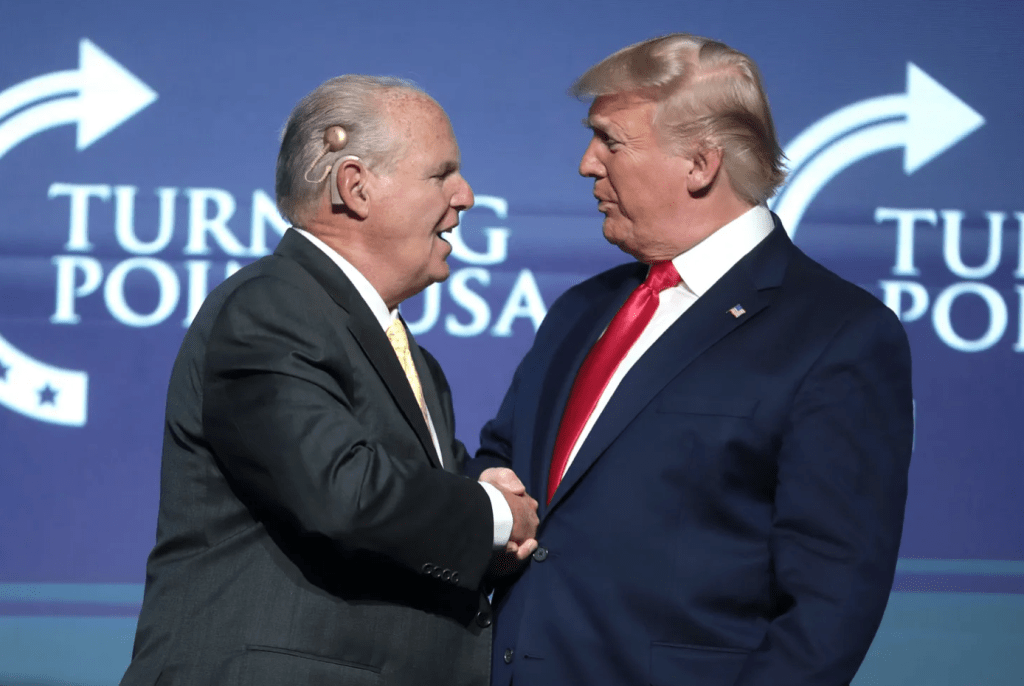

“I don’t need scientific proof — because the people promoting global warming are frauds.” — Rush Limbaugh

In 1778, far from home, shivering and doubtful of their democratic cause, the soldiers of the Continental Army needed more than rations or blankets. They needed fire sent up their spines. To break that winter at Valley Forge, General Washington staged Addison’s Cato — a play about his Stoic hero, iron-willed Cato, who refused to submit to the tyrant Caesar.

Soon after the men watched Cato choose death over submission, word arrived that France had recognized the fledgling republic. The democratic flame was relit, their purpose renewed.

“It is not now time to talk of aught

But chains or conquest, liberty or death.”

— Cato the Younger, Act II, Scene 4

Yet fires are stirred by stranger winds, and whole landscapes yield to deeper forces.

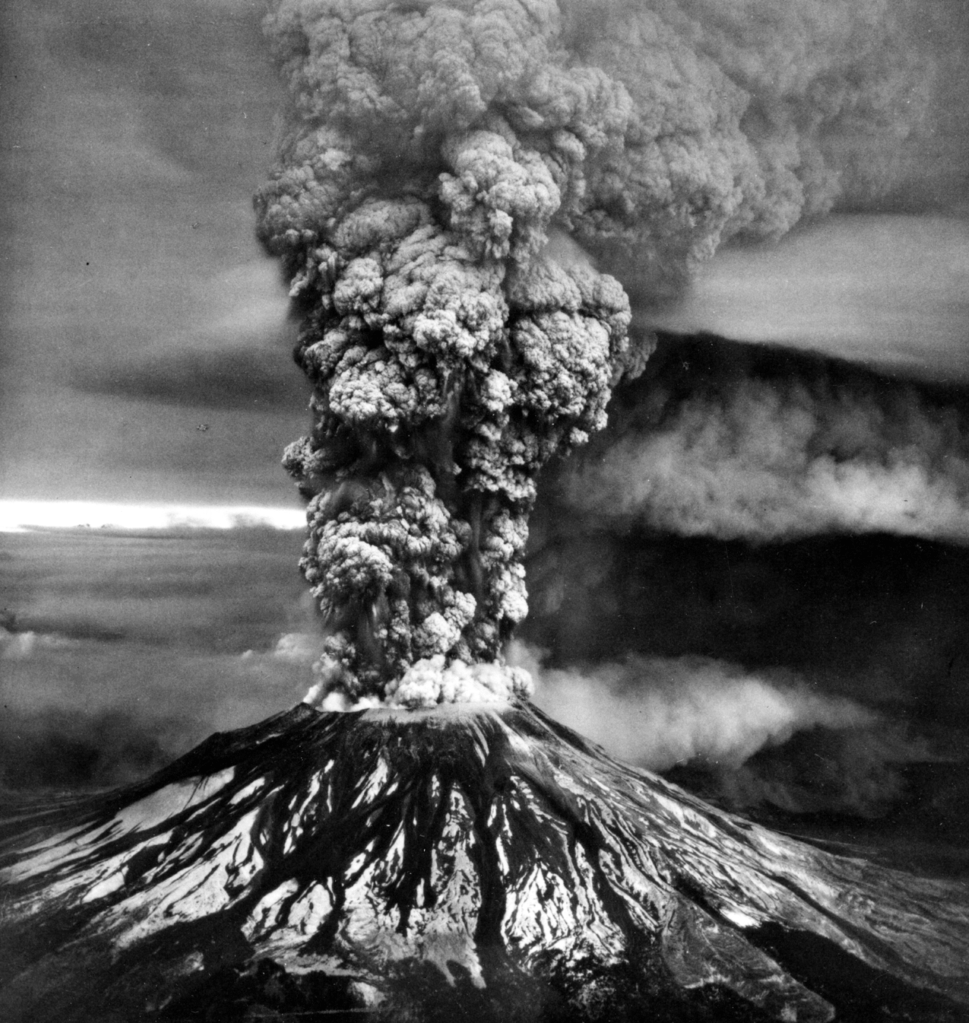

Since that winter of the Revolution’s discontent, and the spring of its revival, just two major eruptions have shaken the continental United States: Lassen in 1915, and Mount St. Helens in 1980 — the first in California, the second in Washington, both along the Pacific Rim of Fire.

In May 1980, the entire north face of Mount St. Helens collapsed, unleashing a lateral blast that flattened 230 square miles of forest — Douglas-fir, noble and silver fir, and western hemlock — all felled in the blink of Vulcan’s eye. An alpine Eden vanished in an instant.

Seven thousand big game — elk, deer, black bear — were buried alive. Countless squirrels, marmots, beavers, and porcupines were swallowed without a trace. Twelve million young birds — eggs, nestlings, fledglings — were plucked from the sky before they ever flew. Frogs, salamanders, garter snakes — gone. Billions of insects obliterated.

The largest avalanche in American history thundered into the valleys, choking Spirit Lake beneath hundreds of feet of rock, soil, glacial ice, and mud. The lake surface rose nearly 200 feet. Every fish floated lifeless, the waters left sterile. The Pacific Northwest itself was forever remade.

As ash darkened the western sky, the decade turned, and the nation stumbled beneath another shadow. This one stretched from the opposite coast: the partial nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island — ninety miles west of Valley Forge, a mere 120 miles north of Washington, D.C.

Existential anxiety had grown colder: just that January, after the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, Carter’s voice rolled out of Washington, declaring that any assault on America’s interests in the Persian Gulf would be repelled by any means necessary — including military force.

Like pressure in the mountain, tensions only built. Day after day that Cold War winter, Americans unfolded their newspapers to grim reports of the Iranian Hostage Crisis. Then in April, the story of Carter’s Operation Eagle Claw exploded across the front pages: a helicopter collided with a transport plane in the Iranian desert, killing eight servicemen.

The wreckage told its own story: soldiers’ lives lost, a mission undone, a nation’s confidence shaken.

And to make matters worse for Carter’s second-term aspirations, inflation hardened into stagflation. Gasoline had nearly doubled during his presidency — climbing from about sixty cents a gallon in 1977 to over a dollar twenty by 1980, with nearly forty percent of that surge in the past year alone. Paychecks shrank as prices soared. By spring, the cost of living had risen 14.4% year over year, while unemployment hovered just above 7%.

Blast after blast buried Americans until they felt entombed, and anything but free.

Then Reagan’s voice erupted onto the scene — not with ash, but with promise — telling weary, worry-worn Americans it didn’t have to go on like this. They did not need to play the stoic. Winter could end. His words reached many like sunlight cresting a mountain ridge, melting glacial ice into streams that sparkled with promise, teeming with rainbow trout and the hopes of blue-collar workers.

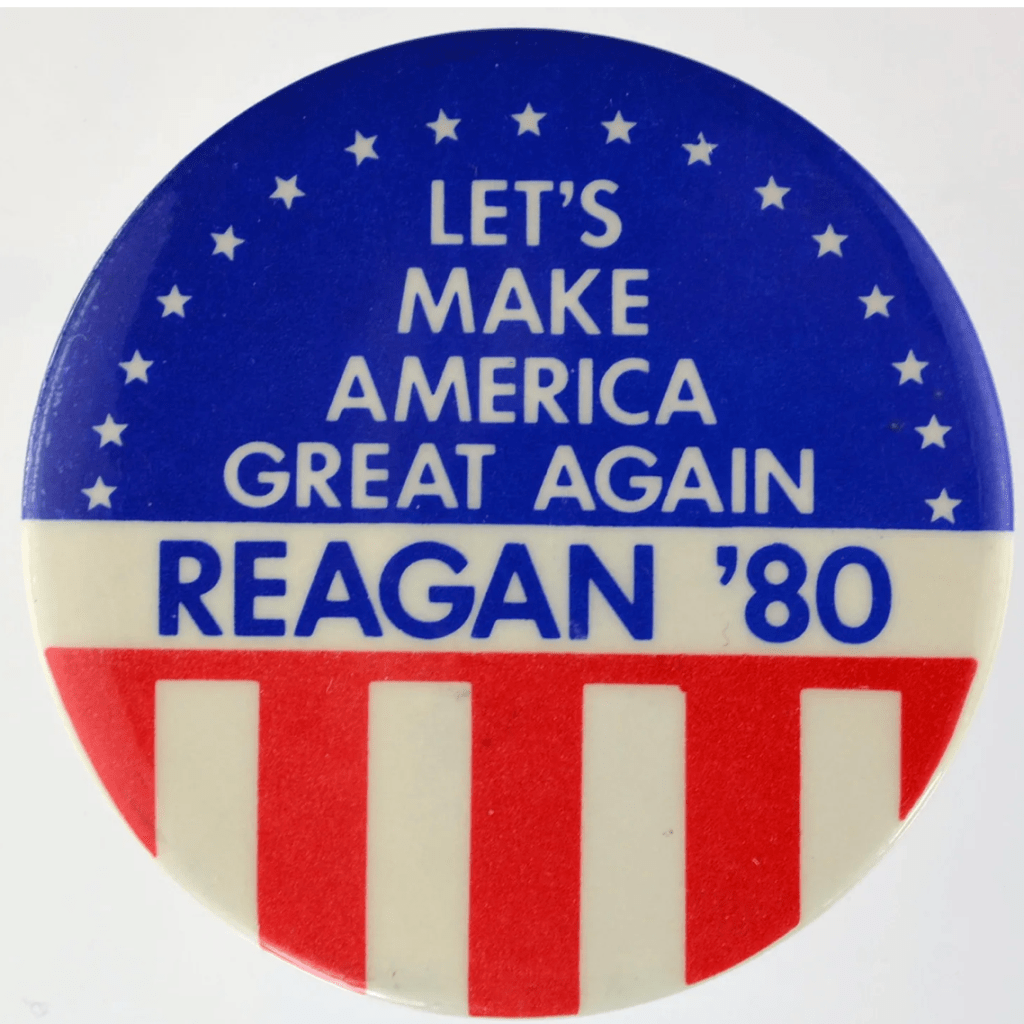

Lured and hooked, few perceived the dark silhouette that loomed behind the cast — a shadow that would stretch for decades — as he told Americans in September 1980: “This country needs a new administration with a renewed dedication to the dream of America — an administration that will give that dream new life, and make America great again.”

Yes, it was Reagan who first promised to “make America great again,” sparking a conservative revolution.

The 1980s found Americans steeped in nostalgia, pining for simpler times. They watched Back to the Future and Happy Days, longing for small towns and jukeboxes. They tuned their radios to “oldies” stations while Coca-Cola told them it was time to get “back to the basics.” And Reagan—the former governor of California and Hollywood actor—embodied the black-and-white wholesomeness of an earlier America. He tapped into this yearning, promising to restore a lost Eden.

Yet Reagan’s morning sun rose a little east of Eden.

Addison’s Cato warned of such seductive virtue: “Curse on his virtues! they’ve undone his country… yet still he smiles, and, like a traitor, wins us with honest seeming.”

Whether they knew it or not, blue-collar voters had been beguiled into voting against their own interests. For many, he was a genial optimist—a Hollywood figure who made the nation feel good again, a warm smile after years of crisis. But beneath that glow lay a harder truth.

Reaganomics buried the poor and widened the wealth gap. He broke unions, handed tax cuts to the wealthy, and left the common waters sterile and starved of oxygen. For working people, the promised garden yielded only thorns.

Worse still, Reagan’s policies corroded the very standards of truth on which the breath of democracy depends.

Even now, I lament the number of our fellow citizens — friends, family, countrymen — whose minds, under the heat of rhetorical smoke and ash, have been vitrified into black glass, like the brain unearthed at Herculaneum: locked away from truth, sealed off from reason. It is a lock no iron key has yet turned, for the key of reason itself lies buried deep in the ashfall of free-market propaganda, where those with the fattest wallets wield the loudest megaphones and the greatest representation — the common good and objectivity alike be damned.

Of course, Reagan is not the sole cause of our lurch into post-truth politics. He had also his virtues — he was, after all, a charming man. Others had been laying the groundwork for years. Conservative institutions — the Heritage Foundation, AEI, Cato, and the Council for National Policy — had long labored to reclaim pre–Civil Rights hierarchies and roll back the gains of women’s liberation. Project 2025, published under Heritage’s banner, crystallizes that project in a powerful push, envisioning a return to older racial orders and a reassertion of patriarchal control — with a distinctly dramatic flair.

Would we had only taken Nancy’s advice, and just said no.

One of Reagan’s capstone achievements in this larger rightward push came at the end of his second term, in 1987, when his FCC appointees repealed the Fairness Doctrine — the safeguard that once required broadcasters to present contrasting views where the public interest was concerned.

Reagan not only supported the decision but vetoed congressional attempts to reinstate the rule, ensuring its demise. In doing so, he opened the floodgates for partisan talk radio, as scholars and journalists alike would later note1. Outrage became currency. “Truth” was now to be measured not by objective evidence but by the loudest free-market belch.

Flawed though it was — vague in standards, uneven in enforcement, and often prompting broadcasters to sidestep controversy — the Fairness Doctrine still required that the media treat public issues with honesty, equity, and balance. It helped ensure that citizens were at least exposed to “the other side.”

As John Stuart Mill put it in 1859:

“He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that.”

Once content was left to free-market profit motives, truth warped, tribalism deepened, and Americans grew less tolerant of opposing views. Ignorance grew endemic, and became both a commodity and a political cudgel — setting neighbor against neighbor, and quietly teaching us to fear one another.

In time, this gave rise to what Governor Cox — speaking in the tragic aftermath of the Kirk assassination — recently called “conflict entrepreneurs”: merchants of ash, outrage, and resentment, profiting by keeping the sky dark.

One of the earliest and most influential was Charlie Kirk’s hero, Rush Limbaugh (1951–2021). Broadcasting from Sacramento, he became a nationally syndicated talk-show host in August 1988 — his microphone turning outrage into currency and amplifying it into a new kind of entertainment economy.

From the shadow of the Cascades, like ash on the wind, his voice spread coast to coast. He mocked science. He scorned reason. He denigrated women. He baited racists. He got filthy rich puffing smoke from his big cigars.

Each broadcast carried a blast of spittle that watered the roots of a tree Reagan had planted when, in 1980, as a candidate he courted the religious right with an apple outstretched in his left hand.

In that gesture he blessed Creationism, invoked “make America great again,” and lured the nation back into a false Eden.

🌈 If you missed Field Note 3¾ — The Rainbow Connection: Don’t Believe Everything You Think, click here.

🫥 If you missed Field Note 3.1 — The Phantom Pronoun: The Fog of ‘They’: Macbeth, Propaganda, and the Aftermath of Charlie Kirk’s Murder, click here.

🎧 Prefer to listen to this piece? Click here.

- Scholars in communications policy generally agree that the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine was not the sole cause of today’s polarized media environment but a significant contributing factor within a wider network of deregulation, ownership consolidation, and technological change. ↩︎

Leave a comment