From Chapter 2, “The Soul’s Ascent”

“No one is more arrogant toward women, more aggressive or scornful, than the man who is anxious about his virility.”

—Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

In our retelling of the myth of Psyche and Cupid, we took note that Venus was a jealous goddess. But she was more than that — she was an institution. An aging one, whose will was carved, it seems, in stone tablets. And like all aging institutions that feel their power waning, she longed to reclaim old glory — to make herself great again.

Her jealousy was pricked by the blue-eyed monster, Envy, as her temples emptied. Once worshiped, the aging goddess now felt sidelined, mocked — even mortal. Public adoration had turned its gaze to a newer, younger, shapelier incarnation.

So the mother sent her son, Cupid, to prick the virgin girl with wild, chaotic passions — and make her fall in love with some irrelevant fool. But the immortal fool lost control and fell in love with the girl himself.

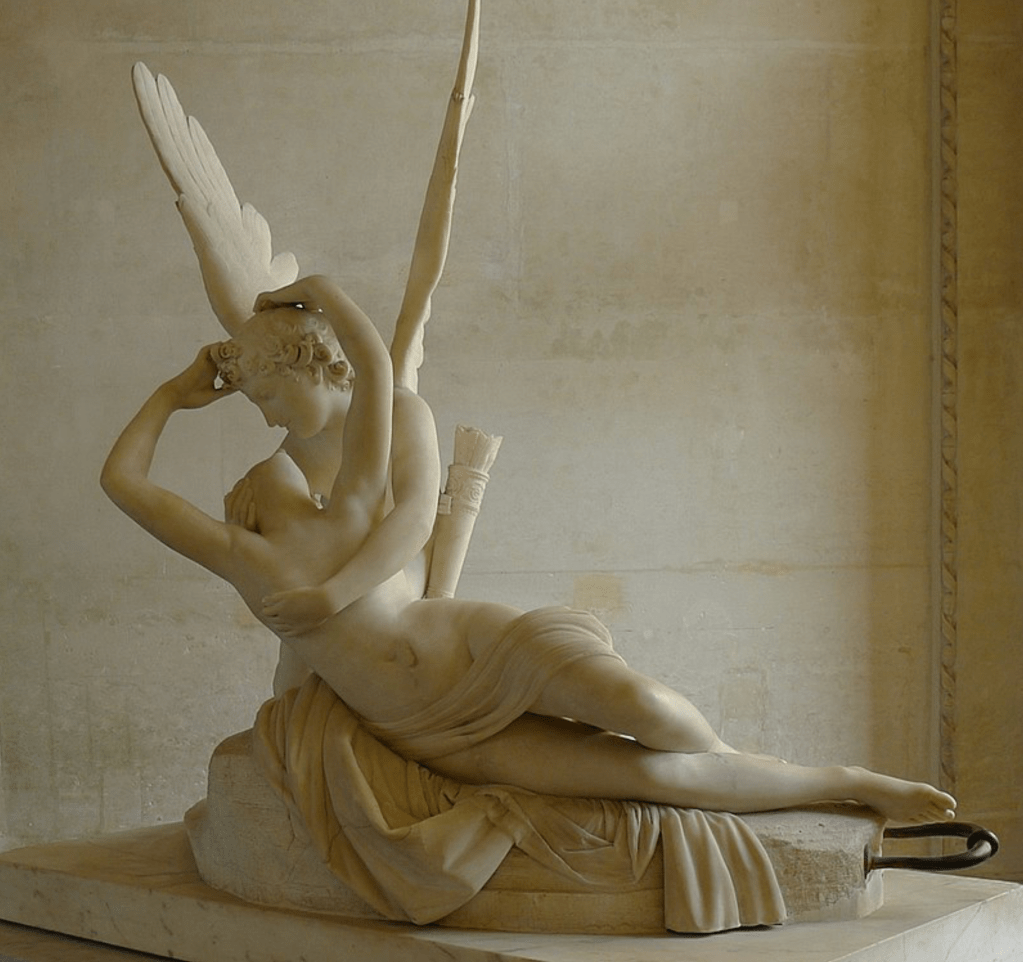

Antonio Canova, Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss. A moment of divine vulnerability: Cupid awakens Psyche with a kiss, losing control — and perhaps immortality — to love. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Now, we might say that Venus is more perennial than immortal. She’s not so much an individual as a universal symbol. She represents something cyclical, something seasonal — something born again with each generation. Keeping this in mind helps resolve the paradox: for a true immortal would have none of the requisite mortal fears to foster that untamable, uncontrollable child of passion — cousin of Pleasure — Jealousy.

You see, Venus feared her temples emptying — feared what it might mean to be replaced by a younger, merely mortal girl. Psyche — whose very name means “soul” — embodied something even a goddess could not command: autonomous will, unsanctioned desire, and the ungovernable becoming of youth itself.

That same fear — of being replaced, of becoming irrelevant — haunts not only mythic goddesses, but mortal institutions and aging leaders alike. It’s as if the ballot box were that same casket Psyche peered into, curious about the beauty it was said to contain.

In the summer of ’24, an anxious America peered into its own ballot box. After his disastrous debate, Biden pulled back and searched his own soul. It whispered what he could no longer deny: the reality of his age. So he did what his rival, even now, refuses to do — he conceded. Time had defeated him.

The president then handed the key to his temple to the next generation, embodied in Kamala Harris. But it was too late. Summer was nearly turning to fall, and she — it now seems — was too female: one who could dance, laugh, and disobey the petrified gender commandments of the broader institution.

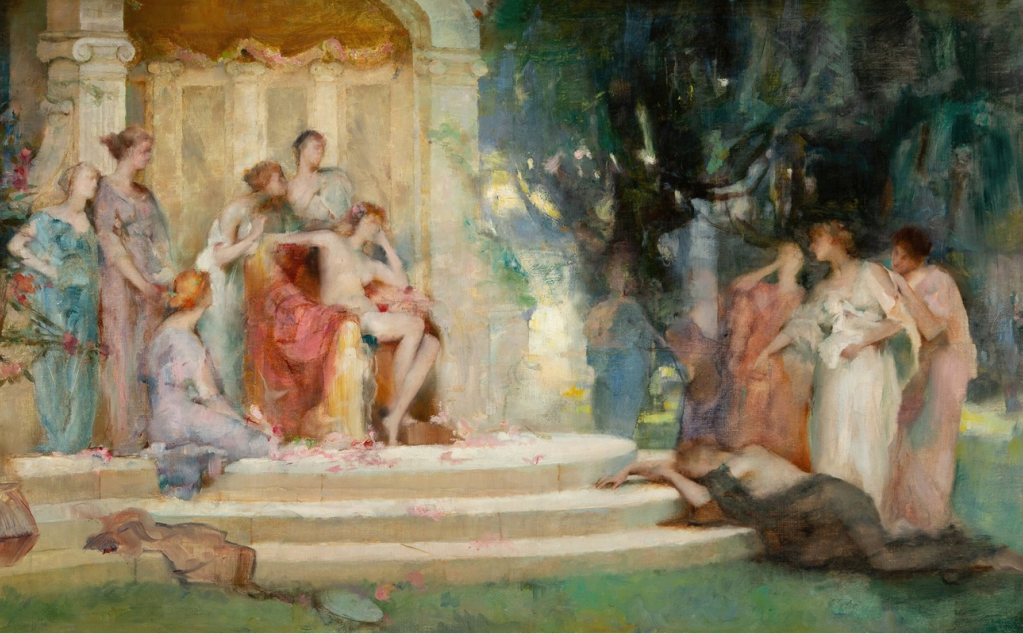

Henrietta Rae, Psyche Before the Throne of Venus (1894). Psyche stands trial—not for rebellion, but for being too radiant, too liberal, too free. Public domain.

In the passionate campaign to elect the first woman to the Oval Office, former President Obama mocked Trump’s “weird obsession with crowd sizes.” He drew attention to the jealous man’s emptying temple, and his inability to gather a swelling audience. With timing and wit, Obama’s hand gesture linked the sparse crowd sizes to the size of the old braggart’s phallus — a jab aimed not just at ego, but at the brittle masculinity that underwrites so much authoritarian performance anxiety.

Trump’s compensatory masculinity is as transparent as it is toxic. From towers to trophy wives, from the “big beautiful wall” to the “big beautiful bill,” he surrounds himself with symbols of potency. It’s all a desperate attempt to gild his legacy and cheat death.

The man famously — almost pathologically — fears his own mortality. A germaphobe obsessed with cleanliness, he clings to rituals of control, as if he could scrub away the body’s slow rot and betrayal. He’s had hair transplants.1 He dyes it. He wears heavy makeup — not just to defy age, but to mask the telltale blush of shame. He avoids the visibly ill and disabled, as if proximity to weakness might expose his own. In his mind, illness is weakness, weakness is failure, and failure is death.

When we speak of Forty Seven, we must hold two truths in view: he is at once a single man — petty, particular, earthbound — and an institutionalized symbol, animated by the fears and fantasies of the broader public imagination, itself fed by existential anxiety. Without that symbolic nourishment, his temple would remain empty. He would be no savior who “alone can fix it.”

In his quest for eternal legacy, we must understand something psychological about the temple itself — and about the adoring crowd who fill it.

The rally stadium is the temple. But it is also the womb.

He is the divine father within that womb — “Daddy,” as his faithful sometimes call him — seeding his legacy, disseminating his likeness. Yet he is also the child curled within it, desperate for protection, longing to be delivered into eternal life.

And the red-cap, caul-bearing crowd?

They are at once his midwives, his vessels, and his children — swaddled in the red caul of his myth of a lost paradise. They help birth his legend, serve as the body through which it travels, and grow ever more expectant for “Daddy” to return and deliver direction and meaning. As one body, they open themselves to receive his image, his seminal word, and give shape to the infantile fury at the damnable injustices done to him — carrying it outward, replicating it in the world.

But this enthroned patriarch is a jealous god — an institution — and he will not abide women tending any altar but his own.

Dare they turn their gaze elsewhere or question his authority, and he calls them “nasty.” To him, that kind of betrayal amounts to infidelity — a threat that suggests his own limitation, defect, fault. And that kind of symbolic cuckoldry he finds insufferable.

Consequently, he demands absolute adoration, worship — the undivided maternal attention he seems never to have received in childhood. This time, he must be the center of all being, the singular ontological truth: the way, the truth, and the life. To turn to another is to defy him — and to re-inflict the primal wound.

And here we begin to glimpse the universal root of the urge to control women.

For a man to transcend himself bodily, he depends on a woman — for he cannot give birth. And for a woman to turn her gaze elsewhere is to declare him finite, replaceable, mortal.

He cannot be The One so long as there is any other one.

To secure his legacy, then, demands a kind of perverse monotheism — one in which the woman’s body, mind, and gaze must be controlled. You’ll have noticed the women in his circle who sing his propagandistic praises: all prettied up, never daring to contradict him, always parroting his “perfect” words. His women must be kept pure, obedient, young, and perpetually ready — so that he might, at a moment’s notice, be fruitful and multiply. Thus he escapes the metaphysical terror of the empty temple, the empty womb, and the abyss of Non-Being.

He must be the only good.

Therefore, pleasure — especially her pleasure, gained by her own volition — is disobedience. An insult. Whether intellectual, aesthetic, existential, emotional, or erotic, her pleasure signals autonomy, agency — and a refusal of the authoritarian aesthetic that demands submission, purity, and spectacle. And that is precisely what makes it dangerous: it asserts her right to choose.

And so, like the serpent — or Eve before her — she must be punished. Cast from the garden. Made to labor in pain.

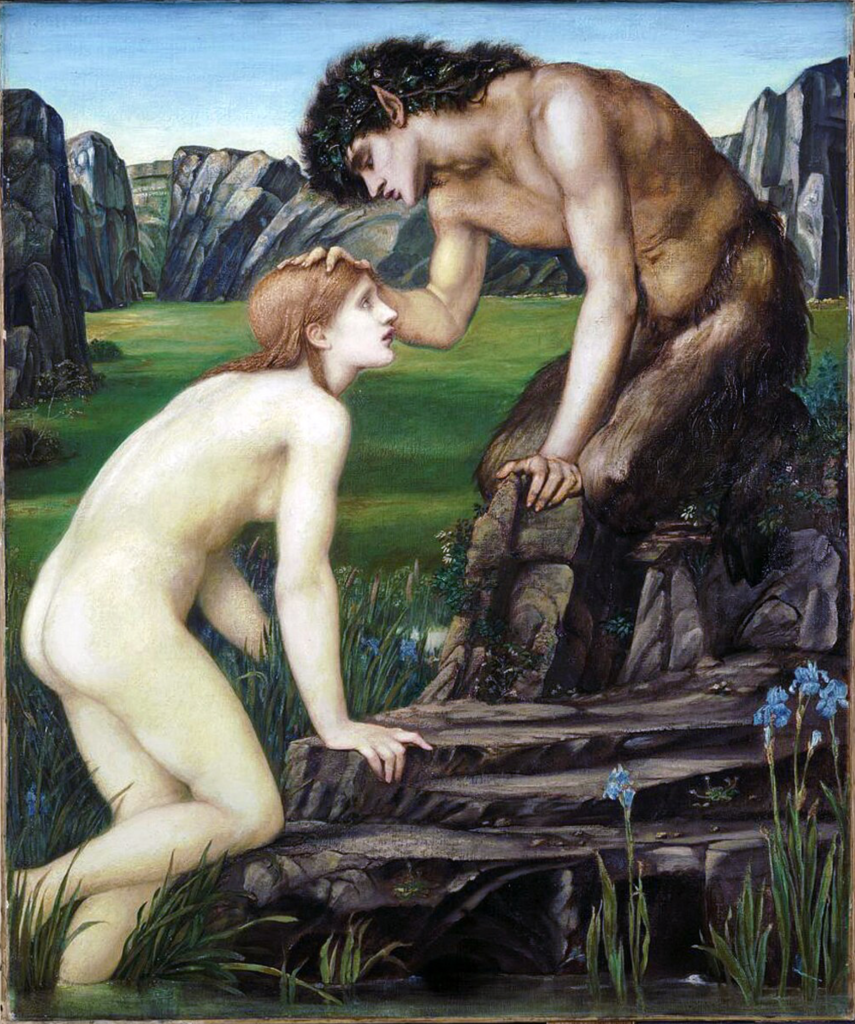

Edward Burne-Jones, Pan and Psyche (c. 1872–74). In a quiet glade, Pan finds Psyche. The gentle male archetype does not punish her, but simply witnesses her sorrow. Here begins the turn: not submission, but struggle; not obedience, but transformation. Public domain.

In contrast, in our myth of the soul’s ascent, fallen Psyche is found by behooved Pan, god of wild nature. Curiously, unlike crowned Venus — the institutionalized feminine — this untamed male does not judge, blame, or bind her in a role. He simply recognizes the universal wound and offers his quiet, humane empathy.

In contrast to the gentle, goat-footed wanderer, it is insecure Venus who imposes the three impossible tasks on the broken girl — trials not of obedience, but of endurance and instinct. Psyche fulfills them not by bowing to the crown, but by following the steady pull of her own independent wit and will. And so, through struggle, she transforms. She becomes whole. She finds joy, gives birth to Pleasure, and ascends to immortality.

✉️ Subscribe on Substack to follow the journey as it unfolds.

Words take time. Coffee helps. Support the writing below!

Leave a comment