From Chapter 2, “The Soul’s Ascent“

We may have inherited our myths, but we choose how we tell them — with which words, and why.

“Art means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner table of the power which holds it hostage.”

— Adrienne Rich

“The moment of change is the only poem.”

— Adrienne Rich, “The Blue Ghazals”

The Greeks — including the great biologist Aristotle — saw in the butterfly a symbol of the soul, of psyche. That ancient association lives on in the scientific name of a gossamer-winged beauty: Glaucopsyche lygdamus, more commonly known as the Silvery Blue.

Glaucopsyche lygdamus, photo by Jacy Lucier, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Glaucopsyche means “blue soul,” and lygdamus is likely a classical allusion, chosen to lend the butterfly a mythic ring — evoking distant worlds and noble lineages. Though its lofty Linnaean name migrated from the Mediterranean, it never passed through Ellis Island. This delicate creature is native to North America.

In the spirit of this soul-name, our inherited Greek mythology tells the story of a beautiful maiden, Psyche, whose journey becomes a quest for soul, self-knowledge, growth, and fulfillment. The butterfly — delicate and ascending — symbolizes her transformation.

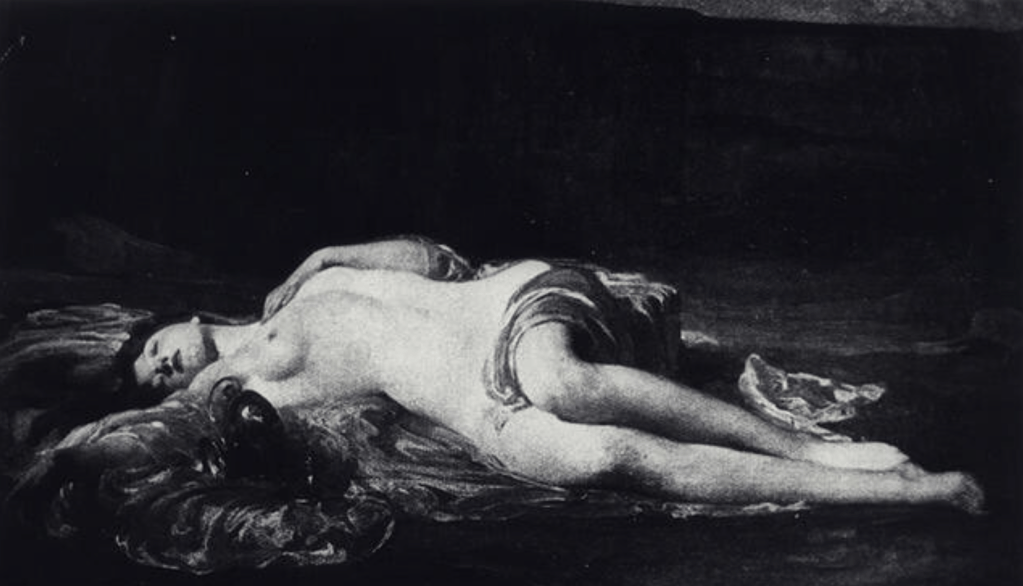

Psyche (1902), by Solomon Joseph Solomon. The soul adrift between worlds. Stolen from the Robert McDougall Art Gallery in 1942, the painting vanished into myth and shadow. Public domain.

Born mortal, Psyche becomes immortal. Born beautiful — the most graceful of three daughters — she draws envy from her sisters. Both have married, while Psyche remains alone.

The source of their envy? Psyche’s symmetry simply stuns men.

The whole world admires her, and people begin to see her as a new incarnation of the goddess of love — whom we’ll call by her Roman name, Venus. As more and more eyes turn from goddess to girl, Venus too grows envious. That her temples now stand empty does nothing to soothe her — for she is a jealous goddess. So the elder woman begins to pace and to plot: she refuses to be rivaled by this mere mortal girl.

Now Psyche’s father — an earthbound king — cannot fathom why his most fetching daughter has failed to find a husband. So he seeks guidance from the ancient Oracle of Apollo. Dreadfully, the oracle speaks: “Dress your daughter in funeral robes. Abandon her on a high cliff. There she will meet her destined groom — a dark, winged serpent of a man, who plagues the world with wild passions.”

Stricken but obedient, the father accepts what must be. And so, he gives his daughter away — not to wed a prince, but to wed her mortal fate.

Then Zephyr, the west wind, lifts Psyche — up, up, and ever higher up — until at last he lays her down, feather-light, in a soft green meadow. There, she drifts into a deathlike sleep.

When the girl wakes, she finds herself on the edge of a cultivated grove. She wanders through it, lost and alone, until at last she comes upon a golden palace. As she stands in awe, the leaves begin to rustle — and whisper around her: Your husband awaits inside, alone, in his chamber. Go to him.

The virgin’s heart pounds — and pulses through her very vision. She hesitates.

Again, the leaves stir, and the whisper coaxes her on: Follow.

Step by tremulous step, the whisper leads her into the palace — through a hall, to a door, and into her husband’s chamber, where not even the moon’s most curious beam can peek. A breeze slips in behind her, and softly latches the door shut.

All grows still, with a silence cold and corpse-like.

In the dark, she senses his presence. Reaching out, she touches him. He winces — almost in pain — at the chill of her mortal fingers. Surprised, she finds his skin nothing like that of a serpent. It’s soft. Smooth. Warm.

“Who are you?” she asks.

With an infinitely tender voice, the stranger replies:

“That, I can never say. Nor do you need to know who I am — if you love me.”

Night after night, he returns to this room — to her. And night after night, they make love in the moonless dark. Invariably, he leaves before the lark can sing.

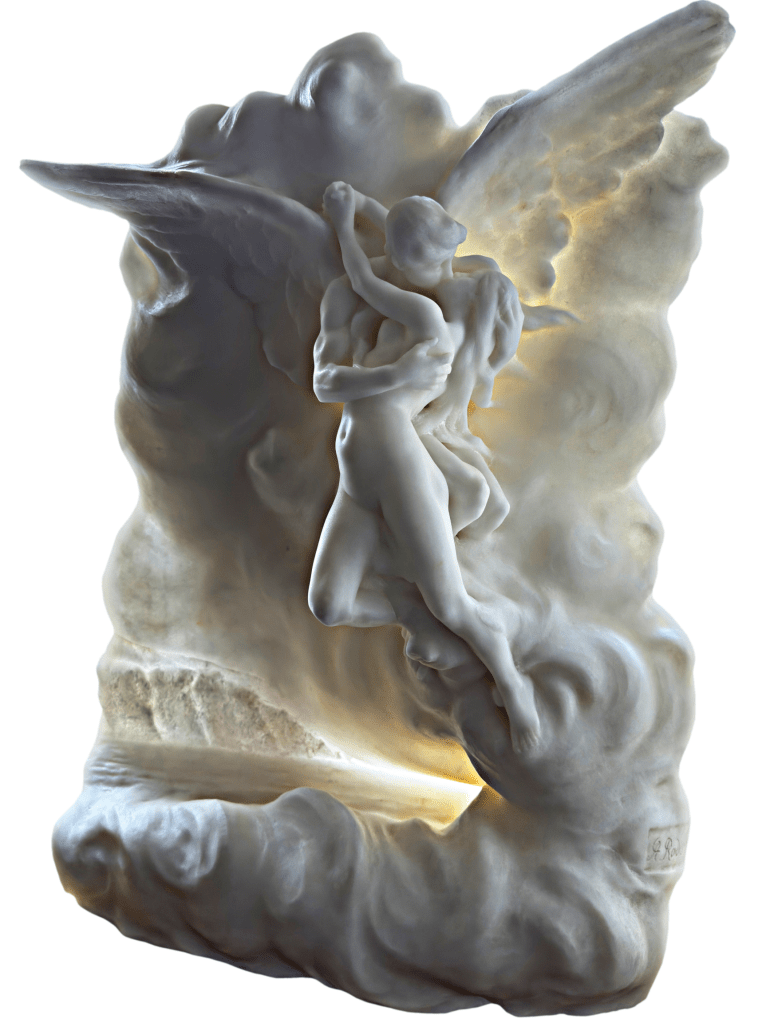

Cupid lifts Psyche into the clouds — a moment of rapture carved in marble. Image by Scu16M (2024), shared under CC BY-SA 4.0.

In time, she finds herself aching for his visits. And soon, her belly begins to swell. Lying beside him in the hush of night, she feels her body glow. And again, the question stirs within her: Who is this? Who is the father of my child?

In the dark, listening to him breathe, she remembers her sisters — envious, cunning. She recalls what they told her when she’d let Zephyr carry them here to visit the palace. They reminded her of the oracle’s warning: that she would marry a winged, serpent-like man — a creature who plagues the world with passion. He will devour you, it had said, and your child.

Her heart jumps again, pulses, this time knocking at her throat. But she cannot swallow the memory.

She sits up in bed, turns, and puts her warm, bare feet to the cold marble floor. As if carried on a moth’s powdery wings, she crosses the room, to her oil lamp — by which she has hidden a knife. She lights the lamp, lifts it, and takes up the knife, her thumb pressed to the hilt.

She turns back to the bed and lifts the lamp. Her shadow slides up the wall behind. Step by step, she approaches him. The ring of light at last reveals his foot, then the curve of his muscular leg, then his chest, and finally, his immaculate face.

At the sight, her breath catches. Her chest lifts with a gasp: she has uncovered none other than Cupid himself — the immortal god of love.

She stumbles back in awe, and pricks herself on the tip of an arrow in his quiver — carelessly cast aside in passion. At once, a fire surges through her veins — wild, unbearable desire.

Reeling, she stumbles. The lamp tilts. Hot oil spills onto his bare skin.

Badly burned, the waked god leaps from the bed. He turns to the window, bends his knees, and spreads his mighty wings — ready to take flight.

But then he pauses.

His gaze drops. Slowly, he turns his head, lifts his eyes — those sorrowful, shimmering, silvery-blue eyes — and meets hers one last time.

Tears streak his immortal face. His heart, broken.

In a voice both tender and trembling, Cupid speaks:

“I am no monster. I have loved you ever since my mother, Venus, showed me your face. Jealous of your beauty, she commanded me to prick you with my arrow — so that you would fall in love with the first mortal fool you saw.

“But when I beheld you face to face, I grew weak. And I understood why she envied you.

“Then you touched me in the dark — and in that instant, I was smitten. So I pricked myself instead… and burned with the foolish fire of mortal passion.”

And now Cupid tells Psyche the truth: they cannot love each other as equals. No, he understands now: never can gods and mortals love that way.

And so he lifts her, turns, and flies out the window into the dark. As she falls into despair, he sets her gently down on the banks of a river — and leaves her.

There, Pan finds her sleeping. And in the lines of her face, he recognizes it at once: the universal wound of Love.

Leaves begin to stir again, and the whisper returns: “Your hope for immortal love is not lost.”

Now grown heavy with child, Psyche sets out to find this love. But jealous Venus blocks the way, and declares that first Psyche must complete three impossible tasks.

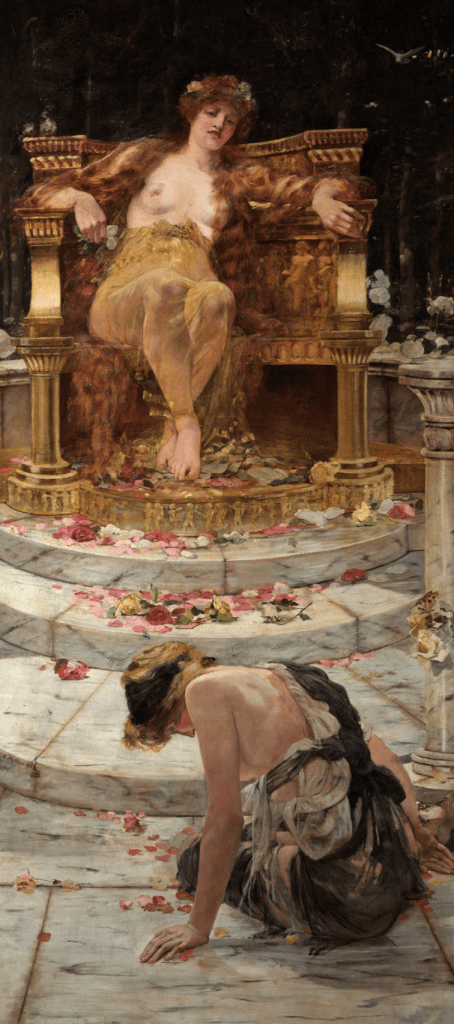

Psyche at the Throne of Venus by Edward Matthew Hale (1883). Oil on canvas. Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum. Public domain.

First, she must sort an enormous pile of mixed seeds before sunrise. She begins the task, but as Dawn’s rosy fingers touch the horizon, her hope begins to collapse. Then a colony of ants, moved by pity, arrive and swiftly complete the sorting.

Next, she must collect golden fleece from the deadly rams. But she knows that these beasts disembowel all who approach. Fear overwhelms her — until a river god shares his secret: “Gather the golden wool caught on the briars where the rams have passed.”

Finally, Venus demands that she descend into the underworld and beg Persephone, Queen of the Dead, for a drop of her beauty, to place in a casket. The road is long, the danger real. Psyche falters. But again the whisper comes, rustling the leaves, guiding her: “Bring barley-cakes for Cerberus, the three-headed hound, and two coins for Charon, the boatman of the Styx.”

She sets the casket before Venus’s palace — but curiosity overtakes her. Perhaps she can keep just a little of this immortal beauty for herself.

She lifts the lid.

But the casket contains no beauty — only sleep.

Psyche collapses.

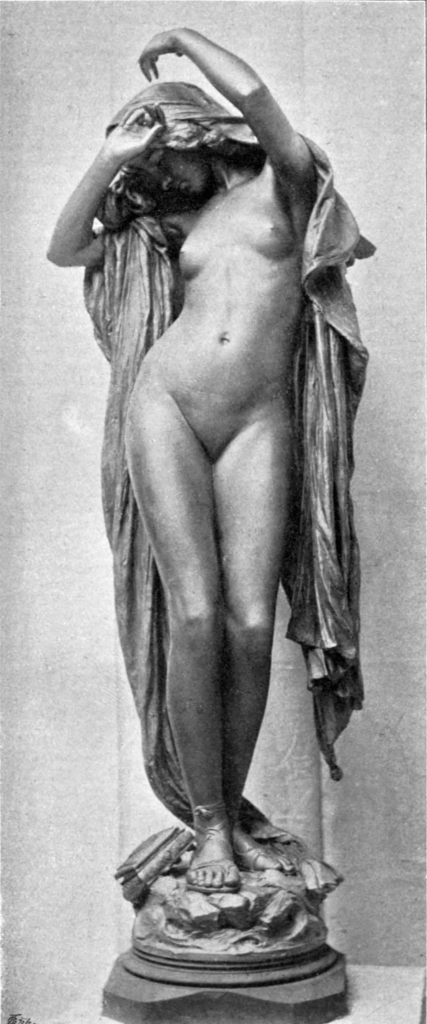

Psyche stands at the brink, weary and near collapse, poised for her descent. Psyche and the Casket of Venus (c.1898) by Horace Montford. Image by ketrin1407, shared under CC BY 2.0.

Seeing his mortal bride collapsed before his mother’s palace — heavy with his child — Cupid rushes to her side. Overcome with love and regret, he confesses his foolishness and tells her: she has proved herself his equal.

Then he offers her ambrosia, the nectar of the gods.

Psyche drinks — and like a butterfly, she transforms. Now immortal, she gives birth to their child.

They name her Pleasure.

Author’s Note

This retelling of the myth of Psyche and Cupid draws most directly from The Golden Ass (Metamorphoses) by the Roman writer Lucius Apuleius, composed in the second century CE — the earliest full account of the tale to survive.

Though Apuleius’s version is Roman, the story’s roots run deep into older Greek traditions. The name Psyche (ψυχή) means both “soul” and “butterfly” in Greek — a layered metaphor embraced by philosophers from Plato to Aristotle. For centuries, the butterfly’s metamorphosis has symbolized the soul’s ascent.

This rendering preserves the myth’s essential shape while retelling it in contemporary language and tone. Certain details — the whispering leaves, the shimmer of silvery-blue eyes — are poetic additions, meant to deepen its resonance within the evolving landscape of No Shortcuts to Now.

At its heart, this version seeks to honor Psyche’s journey not just as a romance, but as a meditation on power, transformation, and the search for self — a mythic echo of questions we still ask today.

How do you interpret the tension between power, beauty, and agency in Psyche’s story — especially in light of Adrienne Rich’s words?

✉️ Subscribe on Substack to follow the journey as it unfolds.

If you’ve made it this far, maybe you’d consider fueling the next step…

Leave a comment